Many Mac users don’t know it, but their computers can speak for them. When famed film critic Roger Ebert lost his voice to cancer-related surgery, he communicated via an American-accented Mac voice named Alex. Apple operating systems come preloaded with more than 50 voices that can read highlighted text aloud in various languages and accents.

Mac voices — also known as “augmentative communication” — are just one of the many 21st-century technologies that have simplified life for disabled people, improving their access to the world and the classroom.

Portions of two major American civil rights laws, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, guarantee accessible education for disabled students in the U.S. Individuals with physical and mental impairments have the legal right to a free and appropriate K-12 education, as well as reasonable accommodations in their post-secondary education.

Schools often meet these requirements by using assistive technology, such as refreshable Braille displays and screen readers that read screen content aloud.

Over at Boston-based ObjectiveEd, which makes educational games, co-founder Marty Shultz recently described one such reader game his company developed. A take on the classic "Hangman," it helps blind and visually impaired students associate the sound of letters with how they feel in braille.

"We’ve now taken the boring task of learning Braille and turned it into a game," he told EdSurge. "We’re changing the dynamic so that a kid is looking forward to learning."

Shultz's game constitutes assistive technology — provided that a student wants to learn Braille. Assistive technology has to "support the function of the individual," says Cynthia Curry, who directs two Wakefield, Mass.-based organizations: National Center on Accessible Educational Materials for Learning and the Center on Inclusive Technology & Education Systems.

In other words, assistive technology is inherently personal.

Curry’s interest in assistive technology has a personal aspect, too. It started during her days as a middle- and high-school science teacher. Although she was well-versed in the subject due to her previous work as an engineer, Curry was bowled over by the variety of learners in her classroom.

“I really had difficulty with learner variability,” she says. “Particularly [with] students who didn't think like I thought. I was working about 16 hours a day trying to make up for my lack of education and training, creating my own materials, trying to work individually with students.”

Her students came from different cultures and spoke different languages. They had different class backgrounds. They also had various levels of physical and cognitive ability.

Supporting kids with disabilities felt essential to Curry, who grew up with a multiply disabled sister. Legislation like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, or IDEA, had made that support mandatory, but it also felt more “straightforward” than “trying to accommodate student variability in language or race or ethnicity, or even gender.”

In other words, equal access for disabled students has a practical component. It can be engineered into existence, in part, with assistive technology.

All Technology Assists

Some critics argue that it’s silly to categorize some technology as “assistive” and other technology as simply “technology.” All technology assists its users, whether we classify them as “disabled” or not. As Sara Hendren wrote in WIRED:

“Honestly — what technology are you using that’s not assistive? Your smartphone? Your eyeglasses? Headphones? And those three examples alone are assisting you in multiple registers: They’re enabling or augmenting a sensory experience, say, or providing navigational information. But they’re also allowing you to decide whether to be available for approach in public, or not; to check out or in on a conversation or meeting in a bunch of subtle ways; to identify, by your choice of brand or look, with one culture group and not another… [A]re you sure your phone isn’t a crutch, as it were, for a whole lot of unexamined needs?”

Not only is mainstream technology assistive, technology designed for those with legally protected disabilities often helps those without them. Or, more generally, improving accessibility for one group improves accessibility for all, in ways we can’t always predict. That's the foundational principle of Universal Design.

One famous example: curb cuts, the ramp-like dips in sidewalks. Originally designed for people in wheelchairs, they turned out to benefit parents with strollers, rollerbladers and a host of other users.

Universal Design for Learning (or UDL) shifts Universal Design’s ideas into the classroom. “It’s based on research on how humans learn,” Curry says. The UDL philosophy goes that lessons designed with accessibility in mind often— “though not always” —work best for everyone, accommodating varied learning styles.

According to a framework first laid out in the 1990s, UDL lessons should represent information in multiple ways. That can be simple enough — think closed caption videos, which make dialogue comprehension easier for the hard of hearing, English language learners and anyone who's absorbing unfamiliar vocabulary.

Evaluation should also let students demonstrate what they know in various ways — in an audio recording, for example, or in writing. Lessons designed to meet UDL specifications often incorporate, or integrate easily with, assistive technology.

The Boston area is not the only place where assistive tech is playing a big role. Check out these eight companies around the country — including Burlington, Mass.-based Nuance — whose products open doors for students with disabilities.

Kurzweil Education

Location: Dallas, Tex.

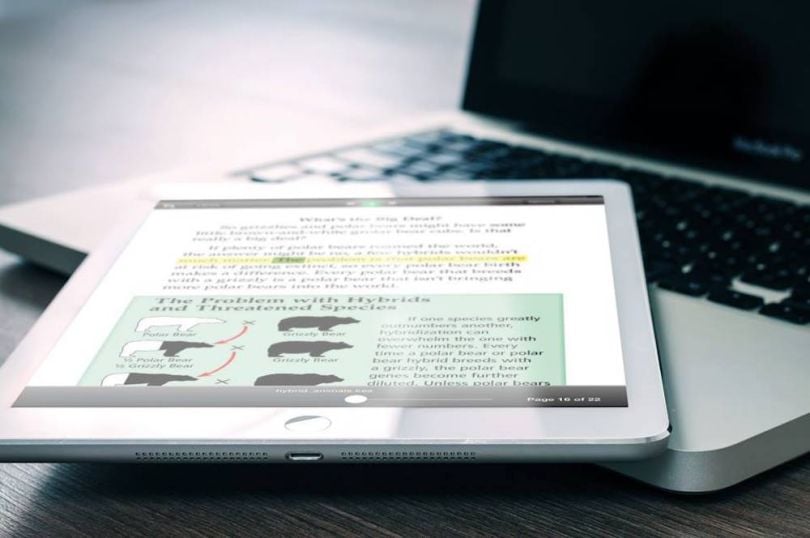

Its signature assistive technology: Kurzweil 3000, a literacy support system for Macs and various browsers, which comes equipped with a variety of assistive technologies. The speech-to-text and text-to-speech functions, which work in 18 languages, help students with vision impairments and ADHD, among other conditions. Meanwhile, a font designed for dyslexic readers, called OpenDyslexic, alleviates letter confusion with its bottom-heavy characters.

Kanematsu Corporation

Location: Minato, Chiba, Japan

Its signature assistive technology: the TactPlus, a Braille printer. Often used by educational institutions, the portable printer precision-heats a specialty foamed paper to create a page of Braille (or other 3D images) in one to two minutes. It’s even outfitted with audio instructions, to aid visually impaired users.

Microsoft

Location: Redmond, Wash.

Its signature assistive technology: the Seeing AI app, designed for the low-vision community, which offers audio guidance in a vast array of situations. It reads text aloud, for instance, as soon as it appears in a smartphone’s camera viewfinder. It also identifies products by barcode when shopping and describes surrounding scenery and its colors. Over time, it learns to recognize the user’s friends and describe their facial expressions.

Crick Software

Location: Northampton, Northamptonshire, U.K.

Its signature assistive technology: Clicker 7, a reading platform that’s outfitted with a whole suite of assistive features. Its mapping feature, for instance, lets elementary-age students create webs of words and emoji-like pictograms, or diagram entire projects. That helps visual learners — which often includes students with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder and Down’s syndrome — tackle reading and writing projects.

Don Johnston

Location: Volo, Ill.

Its signature assistive technology: Co:Writer, a tool that can transcribe speech and predict intended words and phrases — a boon to students with a wide variety of special needs. Produced in partnership with Google for Education, Co:Writer’s built-in prediction engine grasps the fundamentals of grammar and free association, unearthing writers’ meaning even when they misspell words and conjugate verbs incorrectly.

Nuance

Location: Burlington, Mass.

Its signature assistive technology: Dragon, a smart speech recognition software. Though it’s marketed as a business productivity tool, it’s also a widely-used accessibility technology for students with multiple sclerosis and other challenges that make mouse use and typing difficult. Equipped with deep learning capabilities, the software can transcribe natural speech at speeds of up to 160 words per minute.

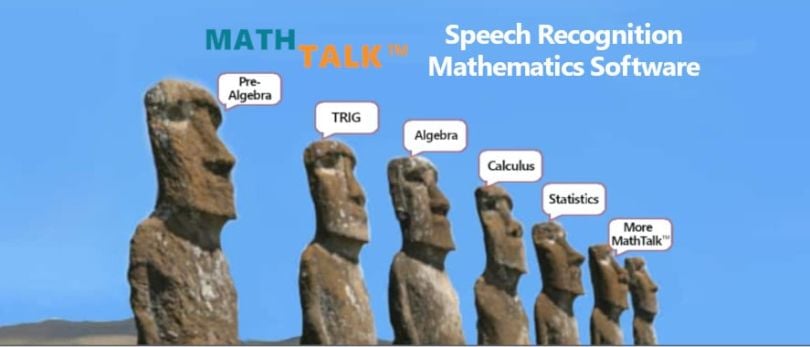

MathTalk

Location: Arlington, Tex.

Its signature assistive technology: MathTalk, a speech recognition software designed for students with ADHD and physical disabilities that preclude keyboard use. An add-on to Dragon (the speech recognition software mentioned above), this software comprehends technical vocabulary and transcribes in mathematical notation appropriate for trigonometry, algebra, calculus and even PhD-level courses.

Tobii Technology

Location: Danderyd, Stockholms Lan, Sweden

Its signature assistive technology: Eye-tracking devices that turn the human gaze into a hands-free mouse. To use the technology, students with limited motor skills and verbal difficulties simply need to look at their screen, and a mix of infrared projectors, cameras and machine-learning algorithms will detect their point of focus.

The Future of Assistive Edtech

Going forward, assistive educational technology has room to grow. Curry sees potential in two particular areas: artificial intelligence and mapping apps.

AI, she says, already has transformed life for people with disabilities. However, "it’s not quite accurate yet under all conditions," and she worries that accessibility programs over-rely on it, especially when working with those who are hard of hearing.

Right now, AI often generates wonky automated closed captions, or live captions for talks. (It might translate “Pokemon” as “bro give mom,” for instance.) AI needs "human monitoring and human vetting" to really work, Curry says.

Once it can work reliably on its own, though, it will transform daily life for people with a wide array of disabilities. Higher-quality AI could not only hear “Pokemon” correctly, but also generate useful tools for autistic people who have difficulty understanding facial expressions.

Many autistic students — though not all — struggle with that, Curry notes. Facial recognition technology, a branch of AI, could help them match a peer’s facial expressions with a feeling and guide them in knowing "how to interact with the individual," Curry said.

Another opportunity for improvement lies in digital mapping. Maps apps already offer users spoken navigation instructions and a highly granular sense of their surroundings nearly everywhere in the world. The maps of the future, however, could support blind people in new ways.

Many blind people memorize the layouts of their neighborhoods and schools and can navigate them without assistance, Curry says. However, unfamiliar environments pose problems. Mapping technology can’t specify which streets have uneven sidewalks and which have no sidewalks. It also can't guide users through unfamiliar buildings — not yet, anyway.

“Augmented and virtual reality could help [blind students] orient themselves in new environments,” Curry says. “And that can be true in smaller spaces, like a learning environment. So students who come into schools — maybe they're transferring from one district to another, or transitioning from middle school to high school — can more quickly and independently navigate their environments."

Of course, that mapping technology would only qualify as assistive for students seeking independent navigation skills in the first place. Assistive technology has to meet the individual’s needs, not the needs that outsiders project onto them.

In that spirit, the ultimate assistive classroom technology — already available, but sometimes overlooked — might be a teacher who asks, "How can I help you?"